Continuing the Conversation on Educator, Artist, Researcher Identities

This blog post by Dr Abbie Cairns shines a light on NSEAD members’ reactions to the recent Educator, Artist, Research (EAR) issue of AD magazine. The special issue emerged from a desire to better understand the layered identities and practices of EARs.

Contributors were invited to reflect on the multiple ways EARs identify, learn, think and live, by responding to three provocations:

- What is an educator, artist and researcher to you?

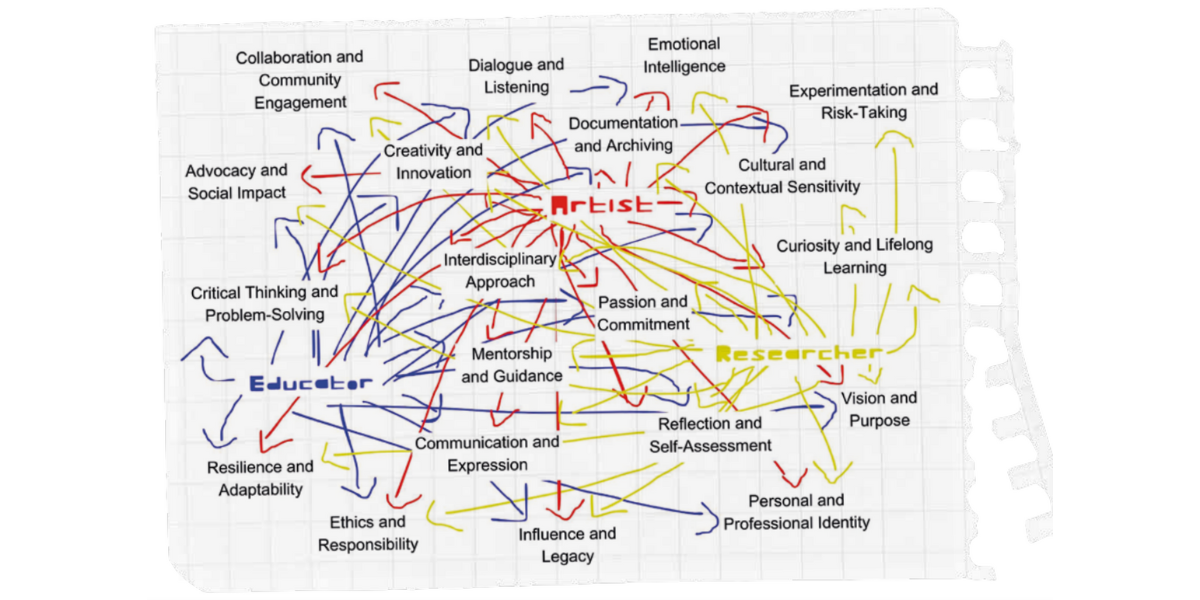

- How does the EAR Worm mapping below help define who we are, how we work and what we achieve?

- How do we start conversations, listen to each other, disseminate and exchange our experiences?

Image: EAR Worm mapping (Cairns, 2024)

_____

A continuous practice of inquiry

Across the responses, one recurring theme is that the EAR identities are not separate but interconnected. As Barbara said:

'The identity of educator, artist, researcher is a continuous practice of inquiry. As an artist, I explore ideas and express them visually; as a researcher, I reflect on methods, context, and theory; as an educator, I translate these explorations into experiences that empower others.'

This sense of ongoing inquiry, of learning through making, reflecting and teaching, was echoed throughout the responses, and Sophie described how being an EAR is embedded in art and design education:

'Every art and design teacher is an educator, artist, researcher – enquiry, exploration, trial and error, trying again, learning and relearning. The identity, the role and subject requires that we are always EARs.'

Here, the creative process and the pedagogical process are inseparable. Teaching becomes another form of making, and research becomes a mode of reflection, resulting in a cycle of practice, critique and renewal.

Interconnection and translation

Several respondents spoke about the interconnection between EAR roles and how one often strengthens another. For Tina, teaching unlocked a deeper understanding of her artistic and research self:

'The artist and researcher part of myself have always been intertwined. I never realised until I started teaching that my education or mentor side would allow for the passion of artists’ process and finding this out to be useful to others.'

This idea of turning artistic and research-based processes into experiences that enable others to learn, points to a defining feature of EAR identity. It highlights how art educators operate as cultural translators, bridging between self and community, individual creativity and collective inquiry.

Visibility and value of research

Others drew attention to the hiddenness of research within art education.

'It is important to be a researcher. This is often not spoken about as an art teacher. I actually don’t consider myself an artist. I do consider myself a creative and an educator.'

This underscores a significant tension: research is intrinsic to the role, yet often under-recognised. For many art educators, research is an embedded, often tacit part of practice, seen in lesson design, experimentation, or critical reflection, but rarely named or celebrated.

Shifting identities and aspirations

Several responses acknowledged the fluid and sometimes conflicting nature of these identities. Hannah shared:

'A multitude of shifting identities. Sometimes in conflict with each other. I am definitely the first two [educator and artist] and aspire to become all three but don't know how this could work beyond the action research I carry out…'

This perspective captures the lived complexity of balancing practice, pedagogy and inquiry. It reminds us that EAR identity is not static, and negotiated over time, shaped by opportunities, contexts and support structures.

A bridge between worlds

The EAR identity also appears to act as a conceptual bridge between different ways of knowing, as reflected by Ellis:

'I feel it draws a bridge and a connection between the traditional ideas and presentations of ‘artistic skills’ and ‘scientific skills.’ The three are intrinsically linked.'

This merging allows creativity and criticality to coexist. It also positions EARs as facilitators of cross-disciplinary learning who inhabit and move between multiple worlds.

_____

Interconnection and flow

For many respondents, the EAR Worm revealed the interconnection between the different aspects of their EAR practice. Barbara wrote:

'The EAR Worm mapping helps me to see my roles as deeply interconnected parts of my inner personality. It shows how creativity, reflection, mentoring, and resilience flow into each other, shaping both my practice and my teaching. The map reminds me that what I achieve is never the result of one role alone.'

This sense of flow, captures the essence of EAR practice. Sophie reflected on how each identity depends on the others:

'The educator, artist, researcher identity is layered, in flux, changing – each requires the other to create the conditions for learning.'

Together, these voices emphasise that the EAR identity is relational. Each role enriches and sustains the others, forming a continuously evolving network of learning and meaning-making.

Chaos and complexity

For others, the EAR Worm mapping represented the chaos of practice, the overlapping commitments and shifting demands that define creative education. Tina observed:

'This is exactly how my three areas feel and look – a mass of tangled and interconnected fun. Being an EAR means I juggle more and feel like my brain will explode with all the good stuff I learn and connections to ideas.'

Another commented:

'This visual clearly shows the multifaceted nature of an art teacher. It also shows an element of chaos to me, and I think the constant shift for art teachers can be chaotic.'

Rather than interpreting this chaos negatively, many saw it as a reflection of the generative potential of complexity, and many embraced the productive messiness that drives creativity and innovation. The EAR Worm mapping becomes a mirror: revealing the beauty of connection and the emotional labour, energy, and adaptability that underpins the work of EARs.

Redefining research

Another thread in the responses was the way the EAR Worm mapping encouraged members to reconsider their relationship with research. Ellis shared:

‘I feel the mapping just further highlights the multifaceted roles we have as EARs. I also personally have felt that ‘research’ was a big word and indeed a big world that I was not a part of. Since becoming kinder to myself and stepping out of my comfort zone I fully appreciate that actually, research can be found everywhere. A fantastic colleague talked to me about how research CAN be artist practice and your own practice as an interpretation of data – or even practice as ‘data’ itself!'

The EAR Worm mapping acts as a prompt to see research not as external or reserved for academia, but as embodied in artistic and educational practice, in the act of questioning, experimenting and making.

_____

Starting conversations through honesty and openness

For many, the starting point for meaningful dialogue was authenticity, and the willingness to share both successes and struggles. Barbara captured this:

‘I believe we start conversations by sharing our practices honestly, including the challenges as well as the successes. Listening to each other means creating spaces, both physical and digital, where vulnerability is welcomed and diversity of voices is valued. We exchange experiences when we move beyond competition and see each other as collaborators in shaping a richer field of art education.’

This emphasis on openness reflects a collective understanding of conversation not as performance but as practice, as an act of care and learning. Within this framing, dissemination becomes less about presentation and more about connection and an invitation to engage and co-construct meaning together. The comments also suggest that starting conversations involves resisting the tendency toward professional isolation. It requires courage from EARs to share unfinished work, to acknowledge uncertainty, and to see conversation as a creative act.

Listening and exchange through practice and collaboration

Several members described how dialogue and exchange often happen through practice, through the making, doing and experimenting that define creative education. Tina shared:

'I have recently done this through a joint passion for ‘the line’ with another artist – the more work we explored together and made together, the more we discovered and had a visual and mental exchange. I studied subjects I had not thought about and vice versa. Through practice we develop each other.’

This example illustrates how collaborative making becomes a mode of listening, where ideas, materials and processes are exchanged without the need for words. It points to the importance of practice-based exchange as a form of research dissemination. These shared creative experiences also demonstrate how learning can occur between practitioners rather than flowing in one direction. They remind us that in art and design education, conversation often takes visual, material and spatial forms, perhaps through shared studios, community projects, or digital spaces where making becomes a form of mutual listening.

Building and sustaining community

Another theme across responses was the central role of community, and particularly our shared NSEAD community, as a vital space for connection, support and collective professional identity. One respondent expressed this clearly:

‘NSEAD is incredibly valuable to me. Their Facebook page is the best CPD I get. It’s such a sharing community space.’

Sophie expanded on the importance of maintaining dialogue and visibility:

‘Keep these conversations going... we need to "own", examine and celebrate our profession and professional identity. NSEAD is a community, a safe community. Let's record, share, create, document our unique, complex but essential role, work and amazing subject.’

This sense of safety and celebration is central to sustaining professional dialogue. It reflects what Wenger (1998) terms a 'community of practice', a collective of individuals who learn through shared engagement. Within the NSEAD community, this manifests through both structured and informal networks: conferences, subject groups, newsletters, social media forums and collaborative writing opportunities such as EAR special issue itself.

Ellis highlighted these multiple layers of exchange:

‘Connect more frequently, debate and discuss, give each other tips (‘have you seen this… have you read this…’) share good practice (‘here’s what I’m doing…’) via structured subject network opportunities, online discussion, and casual and formal sharing opportunities within our own institutions... through publications and writing, on a micro and macro scale.'

Alongside this sense of belonging, Hannah emphasised the need for structure, and practical ways to sustain and extend these exchanges.

‘Via structured subject network opportunities, online discussion, casual and formal sharing opportunities within our own institutions… through publications and writing, on a micro and macro scale.'

These comments encapsulate the spectrum of dissemination, from everyday micro-conversations to formal scholarly publication, and the importance of each in sustaining a vibrant professional ecosystem.

Owning and celebrating our collective voice

The voices here remind us that dissemination is not merely about producing outcomes but about fostering relationships. As EARs, the ways we share, through words, images, artefacts, dialogue, or co-creation, shape how we understand and value our field.

Through honest sharing, collaborative practice and community engagement, we not only exchange ideas but also strengthen our collective voice as EARs. This process of listening and exchange is itself a form of research, an act of inquiry into who we are and what we stand for as a profession. As Sophie put it, ‘Keep these conversations going.’ That invitation feels like the perfect place to end, and to begin again.

About the author

Dr Abbie Cairns is an artist-teacher-researcher who teaches art and related courses in adult community learning, as well as initial teacher education at a university centre. She is a practicing artist based in Essex, working with text and context.

Website | drabbiecairns.com/home

Instagram | @DrAbbieCairns

BlueSky | @DrAbbieCairns.bsky.social

References

Cairns, A. (ed.) and Leach, S. (ed.) (2025) AD Issue 44: Educator – Artist – Researcher. Bath: NSEAD. ISSN 2046-3138. NSEAD members can access an online copy of AD Issue 44 here.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press.