Paper Review by Paul Carney

Education consultant, author and artist Paul Carney reviews iJADE paper 'Making Art Explicit: Knowledge, Reason and Art History in the Art and Design Curriculum' by Neil Walton.

Inferentialism: a theory of meaning and conceptual understanding in which content is understood holistically from its inferential relations. Things have meaning because of their role and function, or from the rules or norms governing that knowledge.

In his paper; Making Art Explicit, knowledge, reason and art history in the art and design curriculum, Neil Walton, Secondary Programme Leader, PGCE art and design, at Goldsmiths University of London, explains that there are competing conceptions of knowledge:

- Cognitive science model of knowledge as information processing & storage/retrieval from long-term memory.

- Knowledge within art education - acquisition of knowledge is seen in negative terms, as reductive, as the imposition of rigid subject content which is opposite to making art.

The paper puts forward the case that knowledge and reasoning is central within the art and design curriculum. He says that improved art education comes out of knowing the historical practices of how and why art was made; that by integrating such concepts in practice and theory we can increase students levels of responsibility and commitment.

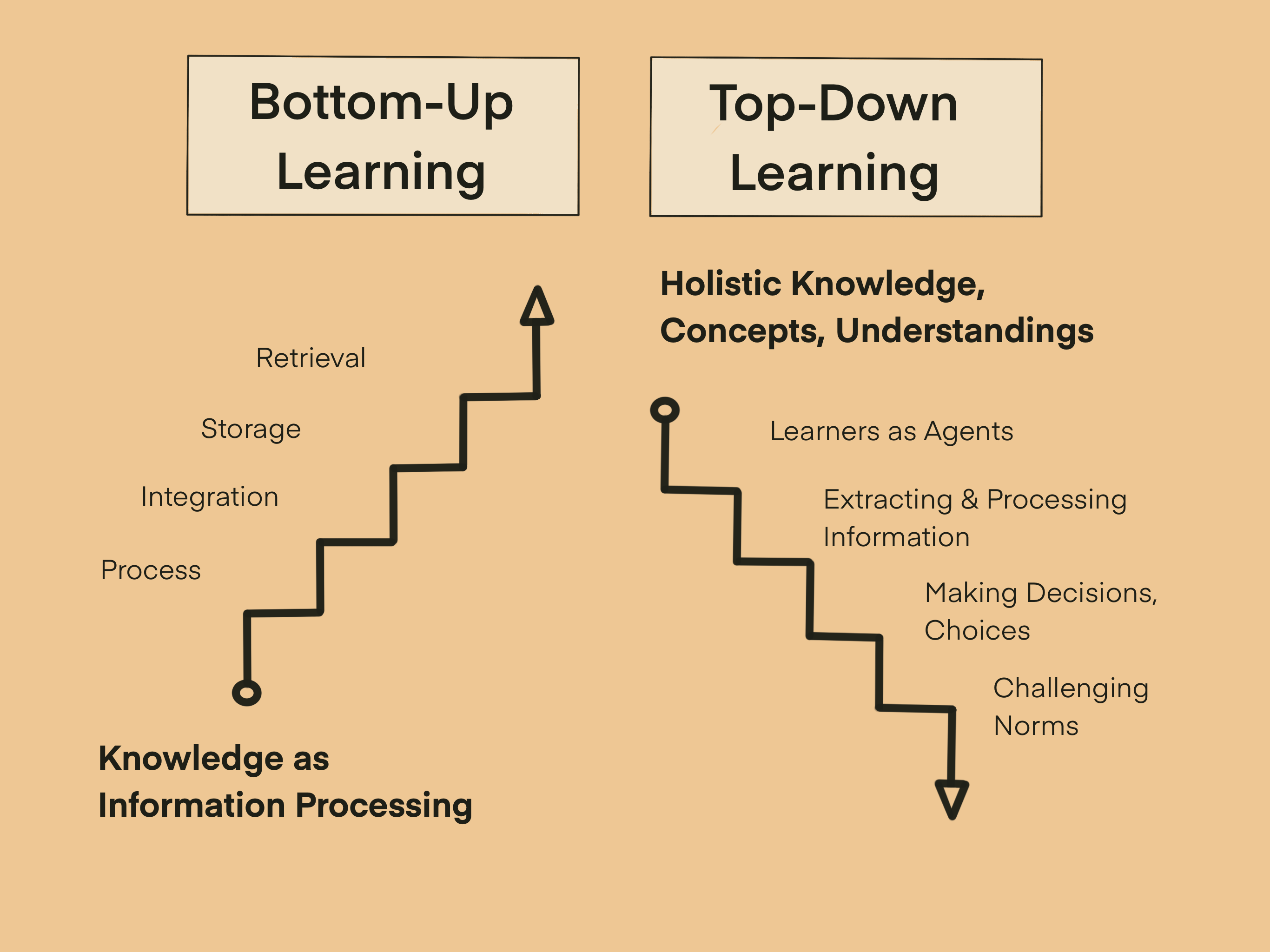

Walton outlines the current explanation of knowledge as a bottom-up model of process, integration, storage and retrieval, supported by the DfE, Sweller and Kirschner, then argues that the evidence for such a model is not derived from subject specific contexts appropriate to art and design.

He says that knowledge in art and design should be seen as part of a wider cultural development of inferential understanding - that a network of related concepts should develop from which the pupil should respond, judge and act when making art. This network is acquired in social situations, holistically, via inferential practices, not in defined chunks or stages. In Walton’s model, learning is a top-down, pragmatic model. He doesn’t rule out deliberate practice and memorisation in discreet chunks but says these should be incidental rather than the main focus.

Learners in art and design he says, make sense of inherited knowledge by extrapolating information from it, sorting, revising and extending it - a process of judging and acting within a shared culture. In this way, learners are agents and doers, responsible for integrating their own concepts and understandings. All classroom practices, he says, are dependent on underlying rules, norms and background properties that need to be highlighted in order to be challenged, integrated or rejected.

To explain this in more detail, Walton uses Eisner’s definitions of art education as direct, personal knowledge; concept formation as a unique perceptual experience. He describes the familiar, staple art room favourite exercise - the formal elements project, where learners examine mark making, or tonal gradations, or colour wheels, to equip them with a foundation of art visual knowledge that they can then later use in their own compositions or analysis. This example is used to show that, if such exercises are performed in isolation, they are fairly meaningless, because they require a context of action - the student must already possess emerging conceptions of art with which to place the formal elements exercises. Waltons says that it is not enough to encounter new knowledge in art and assimilate it, they must be both aware of its context, have choice over it and be aware of the consequences of those choices. Learning should engage the learner, it should require them to make decisions, make commitments, take responsibility, justify and criticise.

To make this easier, Walton has developed a conceptual framework which highlights how historical component views of art are frequently incompatible. When taught, the framework enables learners to critically question and reflect on the choices they are making, encouraging them to position themselves, rationally synthesise and integrate ideas and intuitions into meaningful responses.

Art, he argues, has rules, it’s just that there are no rules about which rules to follow. For learning to occur in art and design, even the most rudimentary exercises must be situated within historical art practice - that everything we do is contextual within what has gone before. With this in mind, acquiring purpose, authority and ownership of art practice stems from, not merely possessing greater knowledge, but having the agency and responsibility to reframe that knowledge in new ways.

Viewpoint

In my opinion, I can see the validity inherent in Walton’s arguments. Teaching discreet packets of art or design exercises in isolation, without proper contextual understanding, has little merit. For example, having year 7 learners complete a colour wheel pro-forma will undoubtedly show them that mixing primary colours will result in the creation of secondary colours, but then they were taught that in Reception, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise. Far better to show some succinct demonstrations on how the human eye processes colour and vision, how fallible it is, and how pigmented colour differs from light-based colour. Contextualising this knowledge with small insights into Isaac Newton, Chevreul, Seurat and Albers, would give secondary learners a better insight into colour theory than a nondescript colour wheel exercise.

This then, is the basis of Walton’s arguments, I think. Whilst I found them at times to be very complex, intellectual, and for me, as a non-researcher, very difficult to access, they nevertheless hit home. I think curriculum designers should derive the content they plan out of the deeper meanings and understandings they want learners to acquire, rather than simply delivering discreet, unconnected units of work.

The knowledge-rich mantra espoused by educational thinkers over the last decade has brought some excellent improvements, in my opinion. I do believe the increased emphasis on curriculum design, combined with more rigorously embedded art and design theory, has improved pupils’ knowledge. I’m also convinced of the benefits of practice and repetition when learning new skills, and the improvements to literacy and language that I’ve seen incorporated over the last few years.

However, I agree with Neil that we must do better when it comes to applying pedagogical thinking. Our curriculums shouldn’t simply involve raising superficial skills or improving knowledge recall, but also involve the ability to make personal, creative responses to complex starting points. This may seem like a tall order, especially when we consider constraints to curriculum time and squeezes on resources, but if we aren’t ambitious, if we aren’t moving forward, we are static, and in doing so, we fall behind.

Personally, I believe a middle-out approach to pedagogy works best for me. This is where both bottom-up teaching of discreet skills is combined in the same unit as top-down, holistic, conceptual understanding. I don’t think one excludes the other, and good curriculum designers will know this. Also, I spend most of my time working with primary colleagues these days, and I’m not sure how much Neil Walton’s arguments will filter down to this non-specialist educational phase, but I do see a sea of change at this level. there is a growing desire to provide high-quality art education, to get their curriculum right, to provide the best education they can for their learners and I’m sure that, with guidance and support, they can integrate much of what Neil proposes.

Read Neil Walton's paper in iJADE early view here:

Supporting graphic: Paul Carney