Teaching noticing in art, craft and design

In this blog post, Teresa Smith shares her reasons for introducing 'noticing' as a key component of an effective art education programme with Primary Art and Design ITE trainee teachers.

The concept of intentionally teaching noticing strategies to learners of art and design is an established one. Deliberate practice in observation - and its sidekick ‘close looking’ - is, and always has been, central to many artists’ ways of working and has therefore long been a focus for the art educator as well. Yet often the physical process of creating dominates objectives and becomes the overriding centre of attention. Noticing, despite often being the groundwork for creating, is easily left behind.

This blog piece shares my reasons for explicitly introducing noticing as a key component of an effective art education programme with trainee teachers on the Primary Art and Design ITE programme I lead. They usually come to the sessions with deeply engrained and rigid ideas of making art, and whilst I want them to continue to develop their understanding of the wonderfully practical and haptic nature of the subject, I also want them to understand that valuing noticing as a distinct fundamental provides strong foundations for any making and creating that follows.

I purposefully use the term noticing instead of seeing, looking or observing. My experience tells me it is all too easy to look at something but not truly register it, or to be too selective about what you register. Whilst these terms may, arguably, be interchangeable, central to my use of the term noticing is that seeing, looking or observing are not always synonymous with interpreting, responding and thinking. The act of noticing that I describe here is a purposeful attention to, and crucially, a making sense of the thing that is being noticed. It can involve a range of sensory input, not just through the eyes, and it requires thought. In the context of art education, noticing needs to be a dynamic verb, a purposeful and positive act.

What are the main benefits of teaching noticing?

Noticing creates awareness.

‘We never look at just one thing,’ wrote John Berger in his seminal work Ways of Seeing (1972), ‘We are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves.’

Disciplined noticing gives students a chance to notice details they may not have seen otherwise, as well as to consider their relevance. Regular noticing practice can train students to be more aware of the world they are in, enabling them to become more attentive, alert, with improved visual/sensory acumen and perceptive skills.

Noticing enables connections to be made, patterns to be spotted, ideas to be shared. Looking carefully at something can help students unravel its complexity, go beyond first impressions and see things from multiple perspectives. When noticing skills are practised together as a group or class, this enables students to connect with each other’s ideas as well as to other artists, to history, to cultures, to society.

As students notice more details, they will also develop an enriched vocabulary as they try to find more precise ways to use descriptive language to describe what they notice.

Images 1 (Left) & 2 (Right). Noticing walks around the local environment, sometimes with a focus theme, can help to draw attention to things that might otherwise be overlooked.

Noticing empowers learners.

Noticing is inclusive; everyone can take part, and no prior knowledge is required. Things to notice are all around us and noticing can encompass all sensory input: sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch; all are equally valuable.

Noticing what is there and what is not there can highlight issues that students may have skimmed over otherwise: when looking at historical art, for example, issues of diversity and gender often come to the fore. Noticing can help us to question ‘the norm’ and be curious and open about the unknown. Noticing and paying attention empowers learners and in doing so increases their ability to affect the world they live in.

Noticing benefits wellbeing.

When we take time to notice, we slow down, which is highly desirable in our media-driven image-saturated world. It can press the pause button. Dossey (2008) tells us that ‘Not noticing is a virus that is loose in modern culture’, driven by the army of ‘surrogate devices’ that do the noticing for us. So, helping students to be mindful and present, to notice extraordinariness in the tiny minutiae as well as the big and obvious, and to learn how to purposefully interact with visual or sensory material that comes their way, this is also part of the job of noticing.

Noticing skills have transferability.

Noticing skills have, for many centuries, sat deeply within the world of art, underpinned by a long history of specialised looking in art history and interpretation. Yet they are helpful within many wider contexts and are a key component of many professions. Noticing can be taught through an art, craft and design programme in a specialised way, yet also without expecting children or young people to become art historians or professional artists.

Six teaching strategies for developing noticing through art

All art educators will have their own bank of activities that support the development of noticing. The key is in the explicitness of why and how we teach them. I share the following tips with my primary trainee teachers:

1. Focus on noticing skills in every age stage

My perspective on this was particularly brought into focus by an article by Torker, in 2021, where he shared this beautiful quote from Slovenian writer Feri Lainšček ‘In that earliest childhood, we get those invisible glasses through which we look at the world all our lives, and these glasses color our views.’ (Lainšček, 2020, in Torker, 2021). Torker was interested in how educators should devote time to developing young children’s observational skills of nature. His arguments on how to progress from everyday to expert noticing included the importance of extended time for careful observations, of teacher encouragement, of ‘conversations between teachers and children, peer interaction, sketching and drawing, sculpture, diary-writing, and asking questions.’ (Torker, 2021). Crucially, the development of noticing shouldn’t be left to chance.

Image 3. The world around us is a treasure trove of interesting things to notice.

2. Match noticing activities with thinking procedures

My favourite prompt for developing those valuable connections between looking and thinking (that is noticing) is the ‘I see, I think, I wonder’ thinking procedure. Thinking procedures like this can help learners to explore what they perceive in front of them in a tentative way, opening up new avenues of possibility. This one is part of a bank of thinking approaches from Project Zero at Harvard; many other thinking approaches could also be used for connecting looking to thinking.

3. Use viewfinders

The small act of framing a scene through a viewfinder has the power to alter perception and attention. Try traditional cardboard viewfinders that help to focus on what is there, as well as alternatives like kitchen roll tubes or mirrors. Be a photographer and do this naturally with the help of a mobile phone or camera. Also experiment with viewfinders that distort or present alternative views of something, like kaleidoscopes or papers that blur or colour the view. Explore different perspectives on the world by moving your body: what might a bird’s eye view of this look like? Or a worm’s eye view? Can you lie down and look up? Stay still for a longer period than you would otherwise. Find a new, exciting perspective.

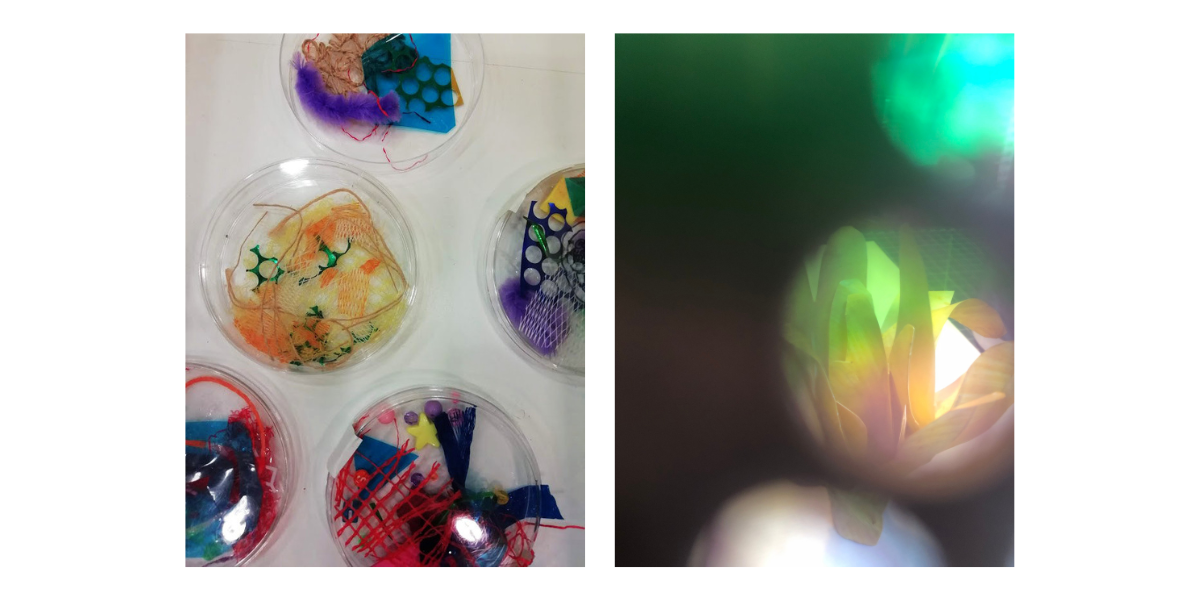

Images 4 (Left) & 5 (Right). Petri dish viewfinders used with a phone camera to distort and frame views.

4. Draw

Drawing something always helps you to notice it properly. The same can be said for trying to write it down in words. Both are great for spotting detail and challenging your natural gravitation to a preconceived schema. The drawing-noticing relationship is often seen as one-directional – that looking helps you to draw - but it can benefit both: we can use noticing to develop drawing skills, and we can use drawing opportunities to develop noticing skills.

5. Adopt/adapt visual literacy programmes

Many museums and galleries have developed ‘slow looking’ programmes and resources, hoping the process of close observation will enable visitors to connect with the works in their collections in more meaningful ways. Art UK’s The Superpower of Looking for primary schools is another example of an accessible art programme aiming to strengthen young people’s visual literacy skills. These programmes take art and visual images as their starting point, but the strategies and approaches can easily be widened out to many other contexts.

6. Engage all senses

When we think of art, it is easy to first think about it as a visual medium, but a single moment in our experience can include multiple sensory stimuli. There is much research on the value of multi-sensory learning, and the best noticers – and indeed many artists - process all of these stimuli in a multitude of creative sensory ways. Each of the senses has a role to play in children and young people’s acquisition of knowledge of the world. Be mindful of inclusive approaches and be wary of inadvertently presenting an unhelpful hierarchy.

Image 6. Sensory approaches, like the small world and sensory items here that connect to a particular painting, can support noticing skills.

Conclusion

Noticing is a natural part of human sense making in our sensorially complex world, and sense making is a critical part of any art education. Noticing engenders curiosity. It can be taught as a powerful tool in an age where noticing skills are increasingly seen as redundant. The world around us is the most accessible treasure trove of things to notice, and so for any teacher wanting to give time and space to noticing skills, we can simply start there. Let us make this often-unnoticed aspect of our art education programmes more prominent, more purposeful, more useful. Let it be noticed.

About the author

Teresa Smith is an artist-researcher-educator with an interest in art as a meaning-making, identity-shaping process. She has previously worked as a primary teacher and an educator in galleries, and currently works in Primary Initial Teacher Education at the University of East Anglia as Art and Design programme lead.

Photograph credits

1. Miriam Jones

2. Teresa Smith

3 (Header). Teresa Smith

4. Teresa Smith

5. Marnie Hardy

6. Teresa Smith

References

Berger, J. (1972) Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books.

Dossey, L. (2008) ‘Noticing’, Explore (NY), 2008 Jul-Aug; 4(4), pp.225-7.

Torker, G. (2021) Taking notice: Children’s observation skills in nature as a basis for the development of early science education, BERA blog, June 2021. Available at: bera.ac.uk/blog/taking-notice-childrens-observation-skills-in-nature-as-a-basis-for-the-development-of-early-science-education (Accessed: 11 March 2025).