Creating a gender inclusive classroom by Amber Smith

In AD Issue 30, Amber Smith, a teacher of art, design and photography at Selston High School in Nottinghamshire, explains how she analysed teachers’ unconscious gender bias and initiated successful strategies to bridge the gender gap. We are delighted to re-publish Amber Smith’s article here on our blog.

Engaging boys in art and design has been an ongoing problem over the years and continues to fuel much research and analysis. As I embarked on my lead practitioner accreditation qualification, I started asking myself some searching questions about potential research projects. Reflecting on my own teaching practice, I realised that, even though I have been teaching for 16 years, engaging and motivating boys remains one of the more challenging aspects of my job. I was, for example, issuing a lot more boys with detentions than girls.

And so, my initial research into boys’ engagement in education began. My first port of call was reading Raising Boys’ Achievement by Gary Wilson. In summary, the points that resonated with me most were how many boys are physically not in a state of readiness to read or write when they start school. The traits that we praise and encourage are most often those exemplified by girls, such as neatness, compliance and listening. Consequently, boys can feel undervalued within education at an early age, which feeds into a negative spiral of low confidence and disengagement. These are all points reinforced by Susan Coles, who evidences this developmental gap on NSEAD’s course: ‘Where have all the boys gone?’

However, it was whilst reading Boys Don’t Try, Rethinking Masculinity in Schools by Mark Roberts and Matt Pinkett that gave me a broader insight. The debunking of previous approaches, which I’m sure many of us have used to engage boys in the past, made me scrutinise my attitude towards different genders in my classroom in a way that I ashamedly admit I hadn’t done previously.

Roberts and Pinkett state that, whilst competition can engage the alpha males within the group, it leaves the majority of the class with a feeling of dejection and lowers levels of self-worth, especially with boys being particularly susceptible to peer pressure. Making learning relevant to boys’ interests results in engagement, but not necessarily learning – it can also reinforce male stereotypes. Roberts and Pinkett argue that there is more of a kinesthetic tendency amongst girls than boys, something which challenged my preconceptions.

The book also promotes holding the same expectations for both genders and subtly celebrating achievement. The one quote that triggered the most thought and initiated the next stage of my research was, ‘One of the best ways to help out boys who want to work, but are cowed by the presence of peer expectations, is to create an environment where there is no alternative to hard work. With challenging groups in particular, providing a quiet, orderly environment for those who want to learn (including those who pretend otherwise) is the only way to do everyone a favour.’

With this in mind, I initially examined strategies we were using within our department that already fed into this ethos. For some time now, we have been using a strategy that we have christened ‘10:2’. The basic premise is that students work in silence for 10 minutes whilst doing independent practical work and are then offered a two-minute break to move around the room and talk.

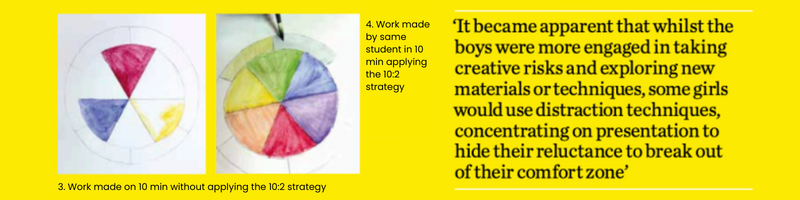

Undoubtedly, the strategy does make a difference to engagement and progress. In images 2 and 4, you can see significantly less drawing has been achieved without applying the 10:2 strategy than progress made in 10 minutes whilst applying the 10:2 strategy, as shown in images 1 and 3. I was now compelled to examine our strategy in greater depth to see the response across the genders. My assumption was that more boys than girls would choose to move around the room during the two-minute break, but as I counted over a wide range of variables, just as many girls as boys chose to move, supporting Roberts and Pinketts’ findings.

The response from the student voice was also very gender balanced. Of the 50 students aged 11–13 who completed a questionnaire, 80 percent of boys and 82 percent of girls said that the 10:2 strategy helped them to concentrate. In keeping with Roberts and Pinketts’ suggestion, it was reassuring to see that we fostering an environment within our department where the expectation ‘offered no 4 alternative to hard work’. Whilst I didn’t want to create a draconian environment, students’ responses assured me that the approach was beneficial and productive. Student voice expressed that the calm environment was conducive to concentrated creativity.

Once I had ascertained that the 10:2 strategy was beneficial across the genders, I also started to look for strategies that would motivate and support learning. Again, a simple approach came in the form of an ‘effort board’. Students’ names were written on the board when they were showing effort to complete the task and then an asterisk was added if they engaged in the challenge activity.

This created a positive and motivating learning environment. It was important that the praise was public, specific, memorable and meaningful, and that the criteria for going on the effort board had value, high expectations, was consistent and not used to manage behaviour. The effort board then fed into the positive points system in operation across the school. As the effort board was established, I perceived a definite shift in attitude as the culture towards learning changed.

Having tried and tested strategies that showed success in engaging and motivating across all genders, I was left considering my own unconscious gender bias and how that reflected in my teaching. Furthermore, as a department of three female teachers, were we gender biased as a department?

I started to ask myself the following questions:

• Do I praise more girls than boys?

• Do I use girls’ work as good examples more often than boys’ work?

• Do I show gender balance in the praise section of whole-class feedback forms?

• Do I show gender balance in artist/ photographer references?

• Do I show gender balance in the display of work?

• Do I accept a lower standard of classwork and homework from boys?

To explore unconscious gender bias further, we also trialled blind marking. Firstly, we filled out a focus sheet as we were marking, then guessed the gender of the student and analysed our assumptions. I’m ashamed to say I did make assumption about the scale of drawings and the neatness of the work. The process definitely shone a spotlight on my gender assumptions and made me appreciate the benefit of blind marking to eradicate any kind of bias or influence of target grades.

Having undergone the process of trailing and sharing strategies, and examining unconscious gender bias within my own teaching and that within my department, I realise that even though we, as teachers, have the best of intentions, it is not until you prioritise an issue that you can fully examine your approach and implement changes. Small changes can have a big impact on readdressing the gender balance within our classrooms. The impact of this on wider society will only become clear if we as practitioners continue to question our unconscious bias.

NSEAD Twilight CPD